I am the Executive Chef at Project Angel Heart in Denver, and I really love my job. It’s an excellent balance of the things I am passionate for: Kitchen work, food, helping those in need, and giving back to the community. You might say this job is tailor made for me. Some have even told me that it was meant to be, my being in my current position; particularly after relating the following story to them. I have to thank our Modified Meals Specialist, Logan, for suggesting I document it.

—–

You know, I wasn’t always a chef. I wanted to be a television journalist at one point. I even went to college for Broadcast Communication Arts at San Francisco State. As a media student, I put myself out there for just about any gig I could get—helping bands load in and out of clubs, working as a DJ at the college radio station; and my most frequent grunt work—helping out local and national news-type entertainment feature shows as an on-location Production Assistant (PA). This mostly meant running cables, setting lights, lugging tripods, checking mics, etc. I usually got paid very little—sometimes just lunch—but I was in it for the experience. I helped on home improvement shoots, golf matches, political debates, news conferences and corporate training films; just to name a few examples.

In 1987, when I was 19, I did a shoot that changed my perspective on life—and helped shape my future.

There was a show called The Home Show on ABC. I think it starred Gary Collins and it attempted to cover everything from gardening, cooking, simple fix-it ideas and arts-and-crafts. It was kind of like Martha Stewart, but with a little Entertainment Tonight and Regis Philbin thrown in for good measure.

I was on their Bay Area PA list and they called me. The call went something like this: “Can you meet a crew in the Mission District at 7:00 am Thursday for a full day, multiple location shoot? You’ll get a show end credit.”

I said yes. Like always.

—–

So on this particular occasion, on a corner in a somewhat sketchy area, I met a director, a woolly camera man (whom I suppose I kind of look like now) and a sound guy outside of a fairly non-nondescript yellow building with the name “Project Open Hand” on the door. I’d never heard of it.

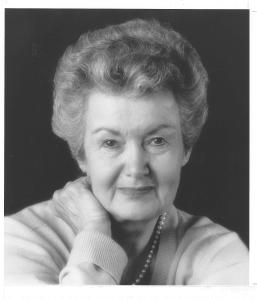

We were welcomed into the facility by an older woman named Ruth Brinker. She was both very sweet and all business. Ruth, as I learned, was the founder of Project Open Hand. Project Open Hand provided via delivery– and still provides– nutritious meals to people who were living with HIV and AIDS.

Now in 1987, “living” with AIDS wasn’t exactly accurate. AIDS was, simply and brutally, a death sentence; and it was only a matter of time before Project Open Hand’s clients would succumb to (more often than not) a slow, suffering, terrible death. There was still a stigma at the time, even in San Francisco, surrounding an HIV diagnosis. I was, now that I reflect on it, highly informed in relative terms (at least with the info available at the time) in regards to HIV, its transmission and its prevention. San Francisco State aggressively provided its students and staff with literature, workshops, rallies, lectures—even condoms (which was borderline scandalous) — to keep the SFSU population in tune and safe.

So, when I was told that on our shoot we’d be, in addition to touring the Open Hand facility, hopping around several San Francisco neighborhoods delivering meals with Ruth and interviewing clients, I was starting to understand that Ruth was a pioneer.

Ruth had seen friends die horribly from AIDS. She saw the effects of the stigma on the morale and will of those who had contracted the disease: family disowned them, friends stopped visiting, they were vilified in their own churches. In short—they often died abandoned and alone. So Ruth acted.

Ruth started Project Open Hand to provide food, this was true. But the visits from the delivery drivers, the conversations, the assurance that they were valued as humans, friends, neighbors and individuals provided a dignity and grace that was so often absent in the denouement of the lives of those with AIDS during the height of its plague-like rampage. When no one else was there, Ruth was.

We went immediately to the industrial kitchen. I believe Project Open Hand provided somewhere around 1000 meals per day at that time. We met the chef named, ironically, Jonathan– like me. I remember thinking, “Wow. A real live chef.”

He showed us the large cooking vessels, the cold and dry storage areas; and, finally, the dish-up line, which was being used by a group of young women.

It was one of my jobs that day to get releases signed by all who were to be on camera. The women, initially, refused. It seemed they were part of a work-for-board program from a rescue shelter; most of them had escaped situations of domestic violence. They were afraid that their former abusers would spot them on TV and come after them. I offered to only film their hands and arms, and they were good with that; although some had to cover distinguishing tattoos with tape.

Ruth explained that the food was designed, mostly, to keep weight on their clients. Most AIDS sufferers had “wasting” issues, and if severe could lead to death sooner than if they had maintained as healthy a weight as possible.

—–

We finished up our tour and headed out on the streets of San Fran. First stop: the Castro District, and a gorgeous apartment right in the district’s heart.

Ruth, meals in hand, knocked. And I thought for sure that Charlie Watts, the drummer for the Rolling Stones, answered the door. Spitting image, no kidding. However his voice, full of flair and all-American, told me Charlie would have to wait for another time to meet me. “Charlie” led us upstairs.

There, sitting on the sofa, was the man we had come to talk to. He had a luxurious red robe on and had obviously just gotten up from laying down. He looked thin, but otherwise I might never had known he was ill.

As we set up Ruth and the director chatted with him. He was a real estate executive, and described the changes he had seen in the Castro. He had known Harvey Milk. He said he could not show his enthusiasm in the same way that he used to before he developed AIDS, but I couldn’t see that. He beamed when talking about his life, about his home about his partner “Charlie,” and about Ruth.

The cameras then rolled. We caught a few moments of this gentleman’s energy that he had displayed during our pre-interview. Then things changed and he began sobbing, “Charlie” fled the room and the man asked us to turn off the camera, which we did.

He admitted trying to put on a brave face; but he was, in reality, scared, bitter and upset. He apologized and we simply said it was OK and for him to take his time. We stood in silence as the man cried and eventually said he was ready to try again. This was the first of several times that day that I—and I believe the others save Ruth—got shaken.

—–

We loaded up the car and took a very silent trip into the Tenderloin District, known at the time for crime, drugs and flophouse hotels. And we pulled right up to one of those very establishments.

As we unloaded, a few people gathered around and started asking what we were doing. We said we were on a TV shoot. Wrong answer.

“What are you shooting?”

“This is our neighborhood!”

“Get the fuck out!”

“You guys always come in here and show how much this place sucks. You suck!”

And then, as I was lifting the tripod out of the car I accidentally tapped one of the people yelling at us in the leg with it.

“Now your ass is getting sued!”

The whole thing just escalated into us trying to maintain our composure, and the crowd growing and getting louder. It was not a good scene.

Ruth stepped up, and led three of the people under the shady portico of the hotel while we stood very close to our equipment. I don’t know what she said, but within a few minutes one of the main people who had been yelling at us came over and calmly told us that he and his friends would make sure our car would be safe while we went inside and did our job. And then he thanked us and shook each of our hands.

Up to the third floor we climbed since the elevator didn’t work. A rat here, some roaches there. I had read about places like this, but I had thought they were a product of Hollywood fiction. Nope.

We made it to our destination and knocked on the door. It took a long time, but then the door opened. And I maintained my cool, but it was not easy.

The man’s arms and part of his face were covered with Kaposi’s sarcoma, a blotchy type of skin lesion common with those who had full-blown AIDS. He had dried pimples and some areas of peeling skin on his face and scalp. He was robed, but otherwise unclothed. Barefoot.

“Come in!” he said cheerfully as he gave Ruth a big hug.

He had seemingly prepared for our visit by clearing a corner of his single room by a window. It had a small desk, a chair and, bizarrely, a tiny aluminum Christmas tree about a foot high atop the desk. It was April.

The rest of the room’s contents had been pushed into the other corners of the room or on top of the bed. Clothes, papers, etc.

He mostly chatted with Ruth as we set up. We didn’t learn a whole lot about him in the pre-interview; but he had obviously had a rough go. He was cheerful and animated as he spoke.

Cameras rolled and the director asked him about how Project Open Hand’s food had affected his life. Like the previous gentleman, he broke down. But he didn’t want us to stop. What he said and how he said it is burned into my memory:

“It’s not about the food,” he said. As he said it, he rolled his hands in the air like he had hold of a volleyball; back and forth, back and forth. His eyes were bright and serious. “It’s about the love.”

Not a dry eye.

“Do you like my Christmas tree??” he asked enthusiastically, breaking the silence.

“Yeah,” said the director. “Is there a story behind it?”

“I keep it up because I don’t want to have to set it up again this coming Christmas. I know I’m going to live to see this coming Christmas.”

—–

We made several other stops that day: Noe Valley, Hunters Point, and then back to the Mission District. The scope was broad in terms of who Project Open Hand was serving— from the swankiest Castro apartment to the seediest Tenderloin hotel.

We all parted ways back at Open Hand. Ruth thanked us, shook all of our hands. We all had words of admiration and thanks for her, and she was extremely gracious. What a lesson I had learned that day. I had been just another ignorant kid from the ‘burbs. My eyes had been a bit more opened thanks to Ruth.

—–

Fast forward 20 years.

I was in a cubicle in Centennial, Colorado, just outside of Denver. I was now the Executive Chef at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station as part of the United States Antarctic Program. The job required 4 four months on site at the Pole. The rest of the time was in that cubicle putting together the one giant food order for the year (which took months to plan and eight C-130s to deliver), hiring the crew, working with logistics, etc. Big job. Big office job.

I needed something to get me back in a kitchen. I also wanted to teach. I had chatted with a cook over cigars at the Pole and he had told me about an organization called Operation Frontline (now called Cooking Matters), which was part of Share Our Strength. He said it was mostly teaching people living on limited incomes how to cook healthy on a budget. Kitchen and teaching. I signed up.

—–

My first class was at a community center in a largely Latino area of Denver. I had a kitchen full of young women, most with babies at their hips. I had a translator and a white chef coat.

The class was going along smoothly, I thought. People were attentive, asked questions and I felt like I was teaching the group something.

Then it happened: I said something, although I can’t recall what. I paused and waited for the translator to tell the group what I had said. Then every woman in the group suddenly perked up. Stood straight, eyes wide. They looked around at each other with surprised expressions on their faces. Had I offended someone? Had I said something stupid?

Then they began nodding in agreement with whatever I had said. And then looked me right in the eye waiting for whatever I was going to say next.

OK, this was another big moment for me.

I had been selfish. I’d volunteered with Cooking Matters to get kitchen work and teaching experience for myself. Selfishly.

Now I had said something that had implanted itself into the brains of these young mothers. Something positive that would potentially affect the health and eating habits of themselves and their babies permanently. This was not about me. This was about the greater good. Like Project Open Hand. Like Ruth. I was hooked.

I volunteered for more classes, I joined the board, I traveled down to New Orleans with Share Our Strength after Hurricane Katrina. I was even Cooking Matters Colorado’s Chef of the Year.

One class I taught was at a place called Project Angel Heart. “Nice kitchen,” I thought as I walked in. I looked into what Project Angel Heart did. Prepares and delivers nutritious meals, at no cost, to improve the quality of life of those coping with life-threatening illnesses.

Well now… Who did that sound like? My memories of that day 20 years prior– of Ruth, of the people we had visited, of Project Open Hand– came flooding back. I became a supporter of Project Angel Heart, joining events and donating money.

Then, after I had decided to seek other employment outside of the Antarctic Program, I saw that Project Angel Heart was looking for an Executive Chef. I pointed out the ad in the paper to my wife, Penny. “This job. See this job? I am going to get this job. There is no one more qualified for this job than me. This will be my new job.”

And I did. I was hired the day before my last deployment to Antarctica. I went down for a month to train my replacement (Project Angel Heart waited for me), and I started at Project Angel Heart still jet-lagged from my travels to the South Pole.

Full circle. I had come full circle from that 19 year old media student, so affected by my single day with Ruth Brinker and Project Open Hand; to the 30-something chef who had come so far from that. There are currently dozens of sister agencies across the USA providing the very services I had witnessed so long ago. We all, however, stand in the shadow cast by the late, great Ruth Brinker and her legacy agency, Project Open Hand.

I don’t believe in fate. But it sure is a good story.